by Michael Buckley

Book 5 in The Sisters Grimm series

Star Rating: 3 out of 4

Book 5 swings into action with Sabrina and Daphne's training to become Fairy-Tale Detectives, and the story keeps the pace up from there. The strange disappearance of the former mayor of Ferryport Landing has led to him being voted out. This leaves the Queen of Hearts in charge and the Sheriff of Nottingham at her right hand, which spells major trouble for the Grimms. The fairy-tale inhabitants of the town have grown tired of their imprisonment and resentful toward humanity, so the Queen decides to level crippling taxes on the human residents of the town, forcing all but the Grimms to move away. The Grimms try to conduct business as usual when it's found that items are being stolen from Everafters, but support for their presence is at an all-time low, and matters aren't helped by the continuing "illness" of their strongest ally, Mr. Canis. And just when they thought things couldn't get worse, strange storms begin to beset the town!

Have I mentioned recently how much I love this series? I mean, besides the obvious cue that I keep reading and reviewing and gushing over them? I feel like I should caution people about starting them because they're so darn addictive. Every adventure is exciting and original and the characters are hilarious. With perhaps one or two exceptions, I love every single fairy tale character usage; Buckley makes them consistent with their tales but still quite modern. I've been waffling back and forth on my favorite character for a while now, but I think the crown finally has to go to Puck:

"We don't want to bother you, but we were wondering if anything has been stolen. Say, something magical?" Sabrina said.The ancient witch shuffled uncomfortably and nodded. "I had a small vial of water from the Fountain of Youth.""Why didn't you ever use it?" Puck asked rudely.

Princess Academy

by Shannon Hale

Star Rating: 3 out of 4

I must confess that I looked at the title of this one and snickered. I can't imagine a book more perfectly named to appeal to young giggly girls. But since it had the Newbery Award sticker on it and all, I decided to give it a try. And I have to admit now that I'm glad I did!

There's a crown prince of the land to be married off, and court priests have "seen" that the princess will come from the small, poor province of Mount Eskel. Inhabitants of the mount spend their days cutting a special stone from quarries there. It's a hard, simple life, and not at all a natural picking place for princesses, but since the bird entrails (or whatever) have spoken, the court sends along a teacher to educate the girls of the town who are of eligible age. The story follows Miri, who is smart and determined, through her time at the academy. Far from being the prissy Barbie kind of read I'd imagined, the book centered around the value of education, leadership, and maybe most of all, community:

The conversation lagged and then stopped, but Miri was too tired and anxious to sleep. She watched the night shadows shift and creep across the ceiling and listened to the low, rough breathing of the other girls. Her pulse clicked in her jaw, and she held on to that noise, tried to take comfort from it, as if the quarry and home were as near as her heart.

I can't express how happy I was at the author's depiction of the changes education effects on the girls. Most go from not being able to read at all to understanding complex concepts like economics. Even better, the girls are able to take what they've learned and apply it in practical, useful ways for their people. There's also a wonderfully mystical subplot concerning the abilities of the Mount's inhabitants and the nature of the stone they cut; aside from being a fascinating story, it serves to ground the characters in that land and make the mountain a character in its own right. There's plenty of fun squabbling and contention in the book as the girls strive toward being the most viable princess candidate, but I found my favorite parts were the ones that took place in the small, homey village. Great read for young teens.

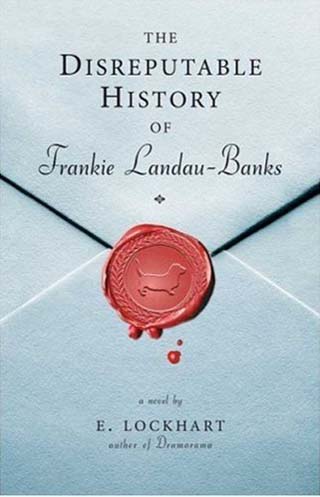

by E. Lockhart

Star Rating: 2 out of 4

I had high hopes here because I've seen this book extolled across bloggorific circles, but it didn't work for me. Frankie is a young girl attending a snooty prep school, and she learns that her father (who also went to the school) was a member of a secret society there known as The Loyal Order of the Basset Hounds. Frankie is curious about the society, especially after she learns that it's an exclusively male society. Purely by chance, she manages to meet some of the crucial members (in fact, she starts dating one of them). She decides that she could do just as good a job at pulling pranks and the rest of the secret society doings as they, and takes matters into her own hands.

This is a book about pretentious people, which I should've known better than to read in the first place because I despise pretension. The prologue to the book is a written confession of Frankie's in which she uses words that aren't really words (i.e., "It is not for me to pugn or impugn their characters"), which is clever/cute once or twice, but she does it like FIFTEEN TIMES in the letter. It's bad when I'm sneering at a book less than 5 pages in. This gets explained as the book backtracks from the confession:

Even the explanation is pretentious. But anyway, I'm not saying the whole book is like that. Frankie is quite clever, though I didn't find her engaging, and her analyses of her contemporaries can be illuminating:When there's a negative word or expression - immaculate, for instance - but the positive is almost never used, and you choose to use it, you become rather amusing. Or pretentious. Or pretentiously amusing, which can sometimes be good.

Expensive clothes and high status had little effect on Frankie. But their money and popularity made life extremely easy for Matthew, Dean, Alpha, and Callum. They did not need to impress anyone and were therefore remarkably free from snarkiness, anxiety, and irksome aspirational behaviors, such as competition over grades and evaluation of one another's clothing. They were not afraid to break the rules, because consequences rarely applied to them. They were free. They were silly. They were secure....and their company is unpleasant. Frankie meets Alpha at the beginning of the book, and later when they run into each other again, Alpha pretends not to know her. Why? We're never told. Matthew, the boyfriend, treats Frankie like a cute little pet and, though she plots behind his back, Frankie lets him. All the conversations with the Basset Hounds guys are peppered with snooty banter, insufferable self-confidence, and ennui. If I met these people in real life, I'd want to punch them in their smug faces. But supporting characters aside, the real dilemma comes from Frankie:

She sat through weekly sessions with the school mental health professional in order to explore her "aggression" and to work on channeling her impulses into more socially appropriate activities. The counselor suggested competitive team sports as a positive outlet, and pushed Frankie to join the girls' field hockey team.And right there, we have the primary dilemma of feminism. If we accept that the society we live in is "patriarchal" -- that is, made by men for the benefit of men -- then the proper feminist solution is to reject that society and pursue an egalitarian ideal. Unfortunately, since that puts you out of the mainstream, you're marginalized and have little power. Conversely, one can work within the current system to gain influence there, but by doing so one tacitly accepts the rules in place.

This was not a productive solution.

It was the girls' team.

Boys didn't even play field hockey.

Boys thought nothing of field hockey.

Frankie was not interested in playing a sport that was rated as nothing by the more powerful half of the population.

Frankie clearly lands on the latter side of the fence: she wants power for herself and is willing to accept the male model in order to achieve it. Maybe this is a practical model. Men *are* the more powerful half of the population, and to get power in this world you may have to play by their rules. So I can't fault Frankie for that. What I do take issue with is that she thinks herself superior because of it. Frankie views the world through the "patriarchal" model and denigrates other females who don't do the same. They're viewed as weak, pathetic, simpering little things. One of Frankie's turning points in the book comes when her boyfriend, Matthew, calls her "harmless". Frankie wants to prove to him that she's not like those other girls, and she does so by distancing herself from them. She spends the whole book hatching plots to prove to the Basset Hounds that girls are as worthy of admission to (and leadership of) their society as boys, and ends up becoming just like them. That's just not a character I'll cheer for.

Whew! Marathon typing. Now I can finally return all of them to the library. I'm currently reading Affinity by Sarah Waters and LOVING it, so I can't wait to post that review!